We Need More Pocket Neighborhoods

Why these unique developments are perfect for houses of worship

Nearly two hundred years ago, Methodists from all across New England would flock to Martha’s Vineyard each summer for religious camp meetings, gathering to worship for weeks on end. In the early days, each family set up a tent, forming a small village that eventually became permanent with the construction of modest cottages. By 1880, the Oak Bluffs community had grown to nearly 500 cottages, welcoming seasonal residents who formed a lasting community. To this day, children roam the neighborhood in the summertime while adults lounge on the front porches chatting and making lifelong friendships.

This is an early example of what some now call “pocket neighborhoods” or “cottage courts.” In his book Pocket Neighborhoods, architect Ross Chapin defines a pocket neighborhood as a “cohesive cluster of homes gathered around some kind of common ground within a larger surrounding neighborhood.” Though the homes themselves are often modestly sized, shared spaces like central gardens and walking paths create a sense of belonging and community.

Pocket neighborhoods are also one of the best models for faith-based housing in the American context.

They offer three key advantages that make them particularly well-suited for houses of worship: adaptability, diverse housing options, and unparalleled community-building capabilities.

1. Adaptability

Pocket neighborhoods can integrate seamlessly into a variety of settings, increasing density and housing options without drastically altering the character of a pre-existing neighborhood. They work especially well as infill projects for low-density suburbs, where a house of worship may have land to develop but faces resistance to wholesale change. Instead, pocket neighborhoods enable incremental density while maintaining privacy and space. A person walking through the area may not even notice the difference from the surrounding neighborhood.

Additionally, pocket neighborhoods can be designed for lots of various sizes. Unlike conventional large-scale developments, these communities make efficient use of land, even on irregular or underutilized parcels. Ross Chapin notes that the best sites for residential development are usually taken first, leaving the more challenging sites for last. While conventional housing patterns struggle with these parcels, the flexible nature of pocket neighborhoods opens up new development opportunities.1

2. Diverse Housing Options

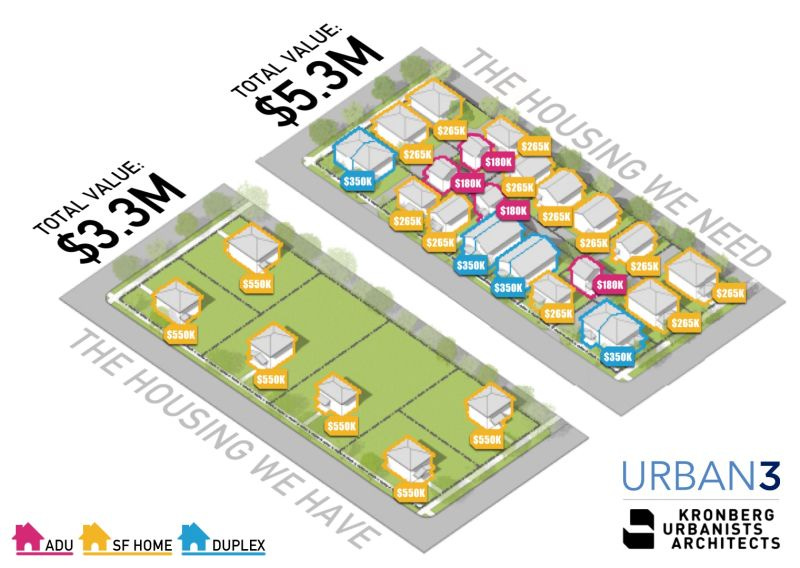

A traditional single-family neighborhood often features homes of a similar size and price point, limiting who can afford to live there and reinforcing economic divisions. Pocket neighborhoods, by contrast, naturally introduce a mixture of housing types, accommodating people at different life stages and income levels.

Houses of worship developing pocket neighborhoods could design homes in a range of sizes and price points, from market-rate units to affordable housing. This ensures a diversity of residents, allowing an older couple, a larger family, and a single young professional to live side by side. By offering a mix of rental and ownership options, faith communities can extend hospitality to those who might otherwise be excluded from the neighborhood.

3. Community-Building Capabilities

The most important aspect of pocket neighborhoods is their ability to foster deep relationships. These neighborhoods are designed for connection: well-placed porches, shared greens, and pedestrian-friendly layouts encourage residents to engage with each other naturally. Children can play safely, free from speeding traffic, while adults form bonds through chance encounters and shared spaces.

A powerful example is ElderSpirit in Abingdon, Virginia. Founded in 2005 by a group of former nuns, ElderSpirit offers 29 homes where seniors can age in an intentional, spiritually rooted community. With both rental and for-sale units, the development ensures a mixed-income population. Though it was originally founded with the aim of fostering spirituality, the community is open to people of all faiths, so long as they commit to spiritual growth and caring for their neighbors.

Why are Pocket Neighborhoods perfect for houses of worship?

These principles are not just about development patterns; they reflect deeper values that all faiths hold at their core. At the end of the day, religion is supposed to give us a deeper sense of purpose and meaning, and part of the meaning we find in life is from our place. Unfortunately, modern development patterns have often sidelined that role. Yet houses of worship have the opportunity to reclaim their sense of place in the built environment. They can be catalysts for creating better places, ultimately strengthening their community and deepening their connection to it.

Pocket neighborhoods offer the perfect opportunity for religious organizations to foster a sense of place. These are not just housing developments—they are communities where people find belonging. Pocket neighborhoods can offer an extension of faith into the fabric of daily life, creating homes where people can flourish together. Whether they are congregation members, low-income families, or elders seeking a supportive environment, residents of pocket neighborhoods have more than just a roof over their head, they have a home.

Eli Smith is a senior at Dartmouth College studying Religion and Public Policy. He is the Faith-Based Housing Initiative’s Research Fellow.

Pocket Neighborhoods, pp 85