The Case for 'Abundance' Christianity

Faith-based housing needs action, not bureaucracy

There is a new idea circling around among the American left: abundance.

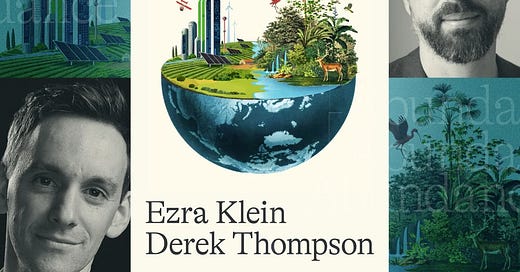

The excitement stems from Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book of the same name, its central thesis being that American liberals have been too focused on perfection at the expense of progress in a timely manner. They’ve gummed up the processes to create anything (housing, healthcare, and infrastructure chiefly among them) with endless studies, environmental reviews, and red tape that makes it an incredibly lengthy and expensive process to get anything done.

This argument is largely a political one, but religious institutions (especially mainline Protestants) have often fallen victim to the same tendencies.

Starting in the mid-20th century, mainline Protestants began wielding their power through government, becoming more politically engaged in causes they believed in. There is no doubt that much good was created through this bargain, but it also introduced the same bureaucratic tendencies that have caused American liberalism to favor stagnation over real progress.

Author and pastor Eric Jacobsen identified this phenomenon over twenty years ago in his book Sidewalks in the Kingdom, where he wrote that mainline Protestants have “hitched their cart to the dominant cultural institutions and have lost some sense of their own distinctive identity as Christians.”1 In cozying up to the dominant power structures, they’ve adopted the same bureaucratic approach, establishing endless committees at all levels.

Everything must be studied in detail, with an eye towards accomplishing many objectives at once rather than one simple task at hand. All of those processes take time and money that isn’t spent on actual impact, and I’d wager few people find them to be spiritually fulfilling. As my friend Evan Magen wrote last week about the relationship between the abundance movement and Christianity, this has led to “status quo bias, an emphasis on the performative over the material, and an unresponsiveness to emerging needs.”

The result? They’ve lost their prophetic voice.

Mainline Protestantism has seen a marked decline over the last few decades, meanwhile evangelicals have seen their numbers stabilize and even grow. They’ve become the dominant force in American Protestantism. There are many reasons for this shift, but I believe that one of them is that mainline Protestants have prioritized procedure and process over results, just as Klein and Thompson suggest about liberalism as a whole. Evangelicals, meanwhile, are confident and forceful in their beliefs and actions, and they adapt quickly to changing circumstances. There’s no doubt that this has its own consequences, but it has allowed them to hold on in a time when many Christian denominations are losing members.

The Alternative? ‘Abundance’ Christianity

How, then, are we to approach this ‘abundance’ movement?

I believe that the way to adapt to the moment is to set clear goals and pursue them with confidence, cutting the bureaucratic process down to only the absolutely necessary in order to see actual results. It is a near certainty that not everyone will be happy–but trying to make everyone perfectly happy is exactly what has resulted in a lack of effectiveness.

In the realm of faith-based housing, this means committing to pragmatism from the get-go, and empowering those overseeing the project to do everything necessary to bring the project to fruition. Certain aspects of the red tape, especially relating to local zoning and code requirements, are outside the power of a single house of worship. But those processes need to be navigated with a clear vision. They’re hard enough to navigate as is; adding layers of internal committees makes them nearly impossible.

I understand that many people may disagree with this. They’ll argue that those processes are necessary, and that they protect everyone involved and ensure that a religious institution is pursuing the right goals. The rules and the committees make sure everyone is on board before major decisions are made, and that’s necessary on an institutional level. Any step back from the current level of bureaucracy, even a controlled one, is bound to be decried as reckless.

The critics may be right in certain regards, but their instincts lead down a path where nothing gets done. Even the small, attainable goals get thrown away because they’re too experimental or because they’re outside the status quo. Bureaucracy isn’t meant to do new things–but right now we desperately need to be doing new things.

We need to be building more housing and in new ways that challenge the system that created our current housing crisis. We need religious institutions to evolve and find new ways to be relevant in our lives, otherwise mainline Protestants will continue our path of spiritual decline. This means streamlining our processes and recognizing that perfect is the enemy of good.

Minimizing Risk, Maximizing Flexibility

I’m not suggesting that we be reckless, rushing into housing projects on religious property without proper consideration and careful design. That would lead to large numbers of failures that the faith-based housing movement can’t afford. But we also can’t afford to never start in the first place.

I propose a happy medium: boldly making small bets.

These small bets can be walked back if they don’t work out, or expanded upon and codified if they do. Lessons can be learned piece by piece, without putting all the eggs in one basket. The traditional approach within faith-based housing (as it is in housing more broadly) has been to do everything at once. Building a large tower with hundreds of units at once is common, but even smaller scale projects often suffer from this. Tiny home projects often do ten or more homes–a number that is certainly small and attainable but still requires significant deliberation and fundraising.

Instead, we need more projects that take a small bite with the recognition that it’s experimental. We need more projects that build only one or two houses at a time, simplifying and speeding up the process. If everyone knows that it’s experimental, the bureaucratic process of deciding if expanding is right for the church can be done after construction with the benefit of the lessons from the first stage. If everyone dislikes the move, it can be backtracked more easily.

This is how we create an abundance of faith-based housing: by taking bold but measured steps, learning from experience, and prioritizing action over endless deliberation. This will require houses of worship—especially mainline Protestants—to move beyond bureaucracy and embrace an outcome-driven approach.

If they do that, they may rediscover the vitality and relevance they have lost.

Eli Smith is a senior at Dartmouth College studying Religion. He is the Faith-Based Housing Initiative’s Research Fellow.

Jacobsen, pp 61

Jesus seems to model the small project. mentality that you write about. What it implies is the ability engage with the people receiving the house instead of just making it an anonymous project. Relationship and dignity seem to be the key to the Jesus model. I think that they also are the key to a successful faith based housing project. When we welcome people into our community at our same level of dignity and respect, we become a healthier community, and a healthier community will produce healthier housing. It is much easier to make an apartment complex with a hundred units for "them" and then criticize if it doesn't work out or if they don't benefit from it. It is harder to sit with people in the challenges of poverty, to see the way our systems contribute to their pain, and to face the decisions of our role in loving our neighbor as ourselves.